In February 1858, Alfred Russell Wallace wrote a letter from the Malay Archipelago, where he was doing field research, to Charles Darwin in England, asking for Darwin’s opinion on a brief essay he enclosed entitled “On the Tendency of Varieties to Depart Indefinitely from the Original Type”. Darwin, who had spent the previous twenty years developing his theory of evolution by natural selection, but had yet to publish it, was shocked to find that Wallace had arrived at a virtually identical theory. He wrote to the geologist Charles Lyell that, “he could not have made a better short abstract [of the book I am working on]! Even his terms now stand as heads of my chapters” (Darwin, 1887, 116). Darwin, at the urging of Lyell and Thomas Henry Huxley (see Huxley entry) arranged for Wallace’s essay to be published along with a brief outline of his own evolutionary theory. He then frantically raced to finish his book, On the Origin of Species, which appeared in 1859.

While Darwin’s notebooks and correspondence clearly demonstrate that he had precedence in arriving at the concept of evolution by natural selection, Wallace’s independent arrival at the same principles based on an entirely separate body of evidence provided one of the strongest cases for the general validity of the theory. Both men followed similar paths to their conclusions. Both were excellent collectors of plants, insects and animals and compared their geographical distributions. Both observed the importance of isolation for speciation, Darwin at the Galapagos Islands, Wallace at the eponymous “Wallace Line” where the Mariana Trench divides Oriental from Australian fauna. Both had read Charles Lyell’s foundational works establishing uniformitarian geology and gradual change. Both made analogies between natural selection and the artificial selection carried out by agriculturalists and pet breeders. And both recognized while reading the economist Thomas Malthus the importance of the over-production of progeny in providing the variations upon which selection could work.

Three characteristics clearly set Wallace apart from Darwin, however. One was that Wallace was unwilling to apply the principles of evolution by natural selection to the emergence of human behaviors, beliefs and intellect. For Wallace, human beings had a moral dimension that set them apart from other animals and this required a soul that could only be imbued by God. Another was that Darwin was educated at elite schools and never worked with his hands whereas Wallace had a working-class upbringing and held several jobs as a teenager, including as a surveyor. Additionally, Wallace was an excellent artist who drew or painted his own specimens while Darwin could barely scratch out a vague resemblance of an evolutionary tree and relied on professional artists and photographers to record his specimens (Prodger, 2009).

Wallace’s surveying work and his artistic ability appear to have been related, although other activities such as making toys, mechanical devices and performing chemical experiments probably contributed (Wallace, 1905, 2-30). Starting in 1838, at the age of fifteen, Wallace joined his brother William in working for a group of surveyors, “copying maps or making surveys” of local estates (Wallace, 1905,130). In this way, Wallace learned to trace maps, correct old ones with new information, and eventually to draw new maps (Wallace, 1905, 144). His surveying and map-making skills would come in handy when he later took off to the South Pacific to collect the specimens that would lead him to the idea of evolution by natural selection. Meanwhile, “At the same time I did draw a little without any teaching worth the name, and I have a high appreciation of good design, and especially of the artistic touch, so that if my attention had been wholly devoted to the study and practice of art, I may possibly have succeeded. But my occupations and tastes led me in other directions…” (Ibid., 261)

A. R. Wallace, pencil sketch of “A Village Near Leicester”, 1844. Reproduced from Wallace, 1905, facing page p. 238.

A. R. Wallace, pencil sketch “Near Derbyshire”, 1844. Reproduced from Wallace, 1905, facing page p. 244.

One direction was teaching. During a lull in the surveying business at the end of 1843, Wallace applied for several teaching positions. He was rejected at the first due to a lack of Greek.

“My next attempt was more hopeful, as drawing, surveying, and mapping were required… I had taken with me a small coloured map I had made at Neath to serve as a specimen, and also one or two pencil sketches. These seemed to satisfy him, and as I was only wanted to take the junior classes in English reading, writing, and arithmetic, teach a very few boys surveying, and beginners in drawing, he agreed to engage me” (Ibid. 230-231).

Teaching quickly wore on Wallace, who was shy and uncertain in public situations and the death of his brother William made him rethink his priorities, so at the end of 1844, he decided to go London to seek new employment. Soon thereafter, he convinced his other brother, John, a skilled carpenter, to join him in a new venture, “thinking that, with his practical experience and my general knowledge, we might be able to do architectural, building, and engineering work, as well as surveying, and in time get up a profitable business.” (Ibid., 244) This work generally involved drawing up plans for renovating or adding on to existing buildings and then carrying out the work (Ibid., 246). In these endeavors, Wallace was aided by a book acquired previously by his deceased brother William, Bartholomew’s “Specifications for Practical Architecture,” which provided practical guidance for the aesthetic design of buildings (Wallace, 1905, 189-190). One of the fruits of this self-acquired skill was Wallace’s design for the Mechanics’ Institute at Neath in the Neath Port Talbot County Borough, Wales, later converted to a Free Library.

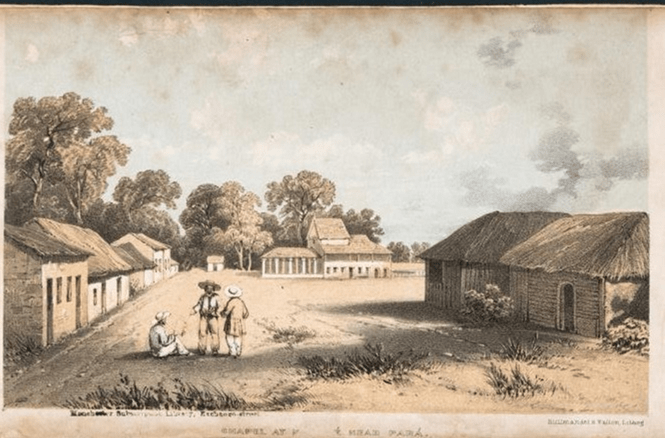

Free Library, Neath, Wales, designed by A. R. Wallace. 1847. (Wallace, 1905, facing page 246).

Wallace and his brother were successful enough to allow Wallace to indulge his dream of travelling to the tropics to collect insects and bird specimens to sell to museums and private collectors. While surveying, he, like Darwin, had become enamored of collecting insects and had begun a correspondence with, Henry Bates, a successful specimen collector. In 1848, they embarked on a four-year collecting trip to South AmericaUnfortunately, the expedition ended in disaster when Wallace’s collection was famously lost on the return voyage. He was able to save only some drawings and sketches.

Fronticepiece of Alfred Russel Wallace: A narrative of travels on the Amazon and Rio Negro : with an account of the native tribes, and observations on the climate, geology, and natural history of the Amazon Valley. London : Reeve, 1853.

Two years later, they embarked again, this time on an eight year expedition to the Malay Archipelago, during which Wallace recorded that he collected almost 250,000 specimens (Wallace, 1869, xv). This material provided Wallace with the insights that led to his independent discovery of evolution by natural selection. One of the most important of these insights results from his map-making skills, which would be valuable throughout the rest of his scientific career as well. Maps pemitted him to identify geographical locations and relate them to species habitats. The most important outcome of this map-making was his discovery of what is now known as “the Wallace line” that divides the plant and animal species of the Asian mainland and the Malay archipelago distinctly from those of the Pacific islands to the southwest. For Wallace, the discovery of this boundary would play the same role in pointing out the importance of geographical isolation on emerging species differences that such differences among Galapagos Island species would play in Darwin’s invention of evolution by natural selection.

The Malay archipelago : the land of the orang-utan and the bird of paradise a narrative of travel, with studies of man and nature / by Alfred Russel Wallace. Original public domain image from Wellcome Collection.

Wallace also used his artistic skills to record not only the birds and other animals he encountered but scenes of live in the exotic lands he visited. Some of these were then engraved by professional artists for inclusion in his books.

LEFT: Drawing of a Flying Frog from Alfred Russel Wallace’s book The Malay Archipelago (Wallace, 1869) based on a painting by Wallace. RIGHT: Wallace, A. R. 1853. Palm trees of the Amazon and their uses. London: John Van Voorst.

After returning to England, Wallace spent his time organizing his material, using most of 1867 and 1868 writing and illustrating his most important book, the Malay Archipelago (Wallace, 1869). “As my publishers wished the book to be well illustrated, I had to spend a good deal of time in deciding on the plates and getting them drawn, either from my own sketches, from photographs, or from actual specimens, and having obtained the services of the best artists and wood engravers then in London, the result was, on the whole, satisfactory” (Wallace, 1905, 406). The original British edition had 52 illustrations of which 13 were from Wallace’s original sketches, including his famous flying frog, as were the two maps (Rookmaaker and van Wyhe, 2015). All of the illustrations in his earlier Palm Trees of the Amazon (Wallace, 1853) had been from his own drawings as well.

In his autobiography, Wallace lists a number of personal defects, among which is an inability to, “rapidly seeing analogies or hidden resemblances and incongruities… while my very limited power of drawing or perception of the intricacies of form were equally antagonistic to much progress as an artist or a geometrician” (Wallace, 1905, 206). The irony is manifest: only an individual with highly developed perceptual and observational skills combined with an ability to think analogically and to recognize patterns of hidden resemblances and incongruities could possibly have co-invented the theory of evolution by natural selection. Perhaps Wallace was too focused on his limitations rather than is extraordinary combination of talents.

References

Darwin, Francis ed. 1887. The life and letters of Charles Darwin, including an autobiographical chapter. London: John Murray. Volume 2.

Prodger, Phillp. 2009. Darwin’s Camera. Art and Photography in the Theory of Evolution. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Rookmaaker, Kees, and John Van Wyhe. 2015. “The Illustrations in A. R. Wallace’s Malay Archipelago (1869) and in a Much-Enhanced French Translation in Le Tour Du Monde (1870-1873).” Archives of Natural History 42 (2): 358–62. doi:10.3366/anh.2015.0321.

Wallace, Alfred Russel. 1853. Palm Trees of the Amazon. London: John van Voorst.

Wallace, Alfred Russel. 1869. Malay Archipelago. London: Macmillan, 2 vols. https://darwin-online.org.uk/converted/Ancillary/1869_MalayArchipelago_A1013.1/1869_MalayArchipelago_A1013.1.1.html

Wallace, Alfred Russel. 1905. My life: A record of events and opinions. London: Chapman and Hall. Volume 1.

All of the illustrations shown here (and many, many more) can most easily be found at https://wallace-online.org/thumbnails/Wallace_Online_Illustrations.html and are open access and free to reproduce.